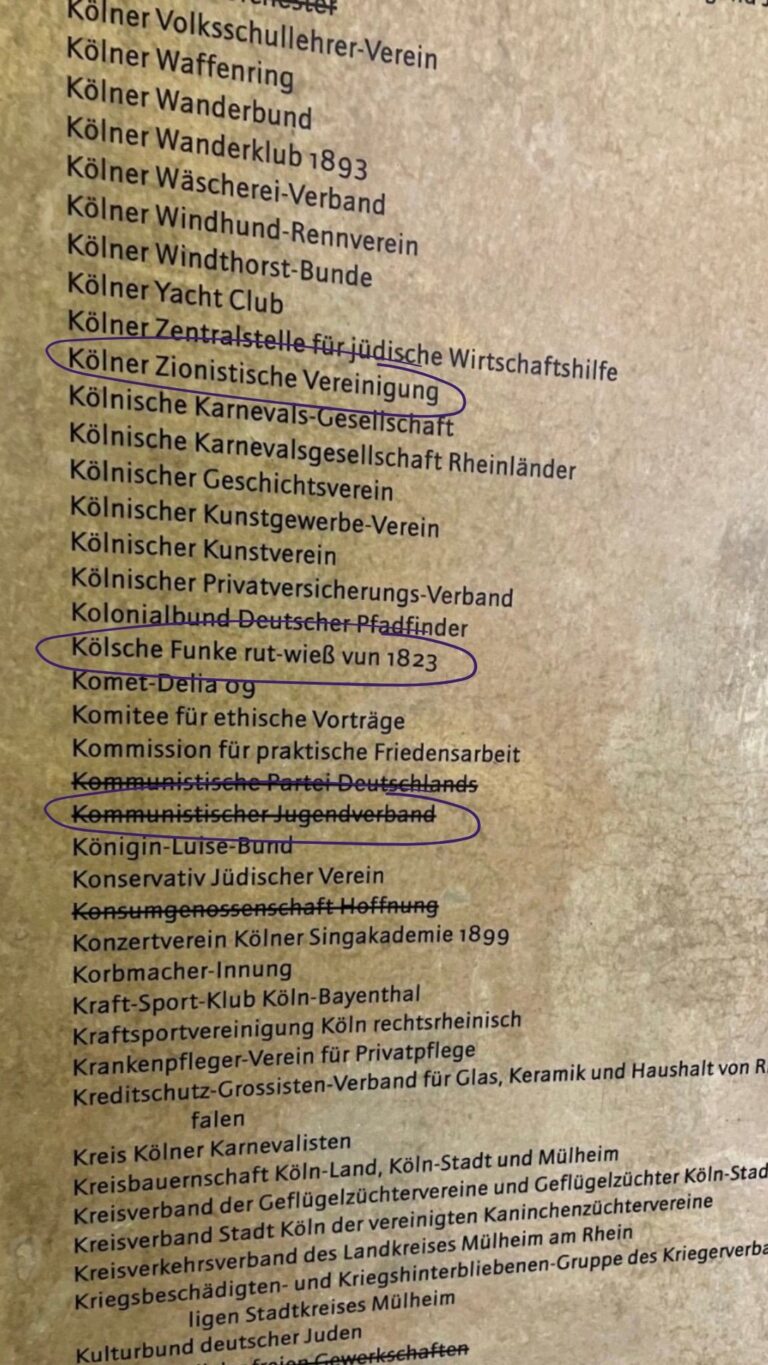

Look around! Can you find the ‘Kölsche Funke rut-wieß vun 1823’ (literally: Cologne’s Red-White Sparks of 1823) in the list?

The Rote Funken carnival club has a long history. In the 1930s, many of the club’s members were merchants or tradesmen. They were organised into fixed club structures and had a board of directors and a senate. With their red and white uniforms, they traditionally mocked the Prussian military during the Carnival.

The club is not crossed out here. This means that it continued to exist after 1933 – in contrast, for example, to the Communist Youth Association (KJVD), which you’ll find crossed out a few lines down. The KJVD was banned in 1933 and many of its members were persecuted. Jewish organisations, such as the Kölner Zionistische Vereinigung (Cologne Zionist Association) were not banned until later – although their members were already subjected to anti-Semitic attacks prior to that point. Many non-Jewish associations, on the other hand, continued to exist; they were gleichgeschaltet, or ‘brought into line’.

But what did that mean in the case of the Rote Funken, for example? What do you think?

You can choose multiple answers.

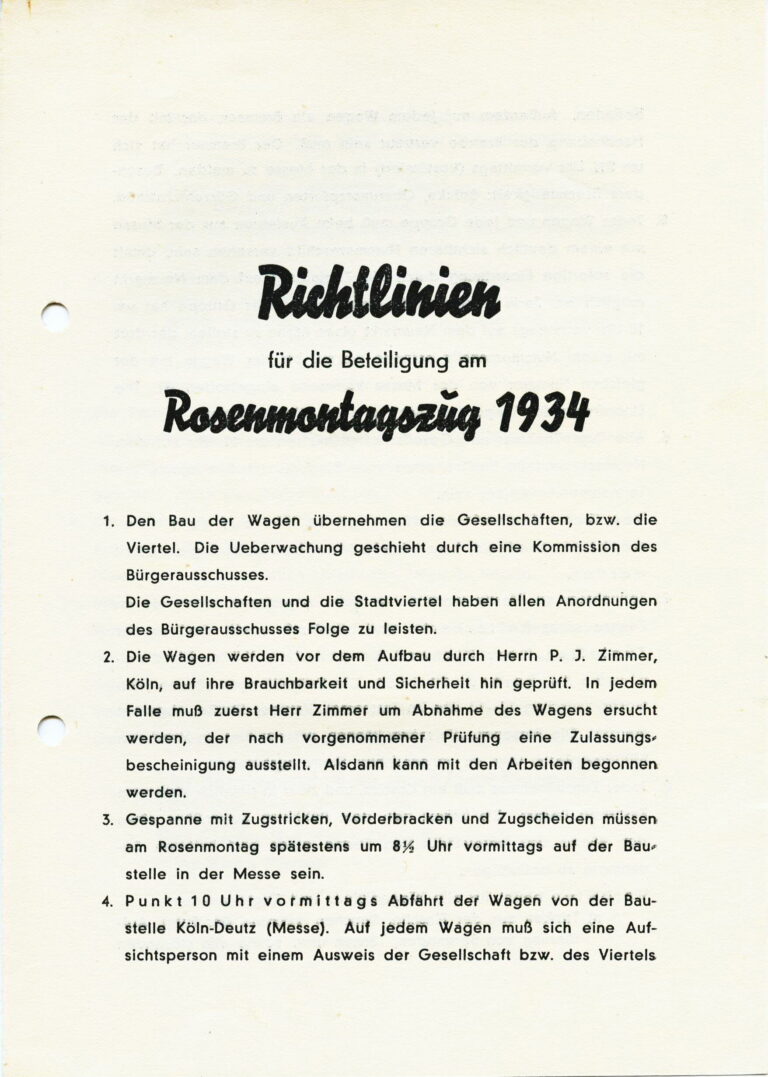

As a matter of fact, committees supervised the construction of the floats for the Rose Monday Parades. However, it is incorrect that only Nazi Party members could be elected to the board of directors. Nor did Jewish members have to be immediately expelled, although a few clubs did so on their own accord. Moreover, some of the criticism of the regime’s influence was vehement.

The clubs were not affiliated with any Nazi organisation, but their supervisory bodies – the festival committee and the citizens’ committee – were brought together under an umbrella organisation, the Cologne Tourist Association, which had close ties to the Nazi Party.

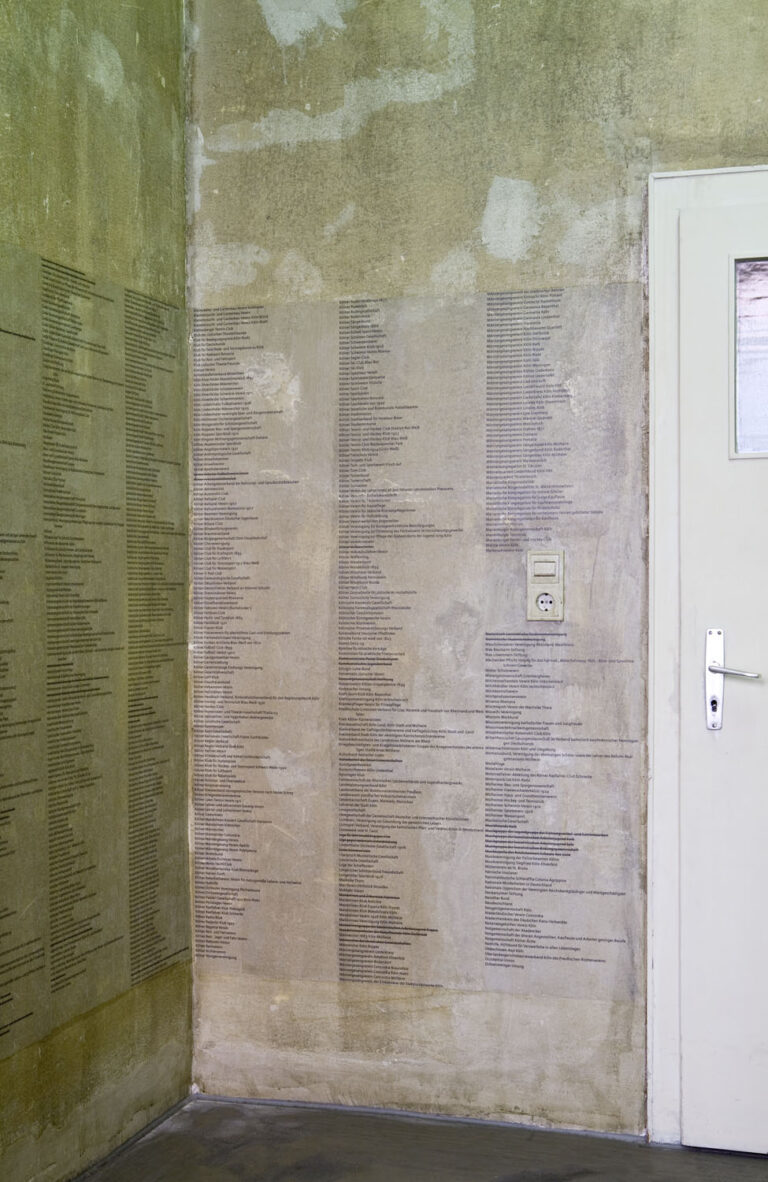

To this day, it is widely believed that the Nazi regime was able to completely control Germans’ leisure activities and club life. This room, too, can lend the impression that associations were either banned or became National Socialist.

In fact, however, it is more complicated than that. Various authorities and party offices did indeed try to shape the Carnival, for example, according to their own ideas. But they had no control over the carnival clubs, which were largely independent.

The case of the Rote Funken shows how, as in many associations, there was an interplay between the demands of the regime and the activities of the club itself.

The case of the Rote Funken shows how, as in many associations, there was an interplay between the demands of the regime and the activities of the club itself: the new political order established in 1933 opened up many opportunities for action, which club members used to their advantage – whether to strengthen their own position within the club or to compete against other associations. And one’s own role in National Socialism was very much the subject of heated debate, especially in the early days.

Take a look at one or more stories from the club life of the Rote Funken.

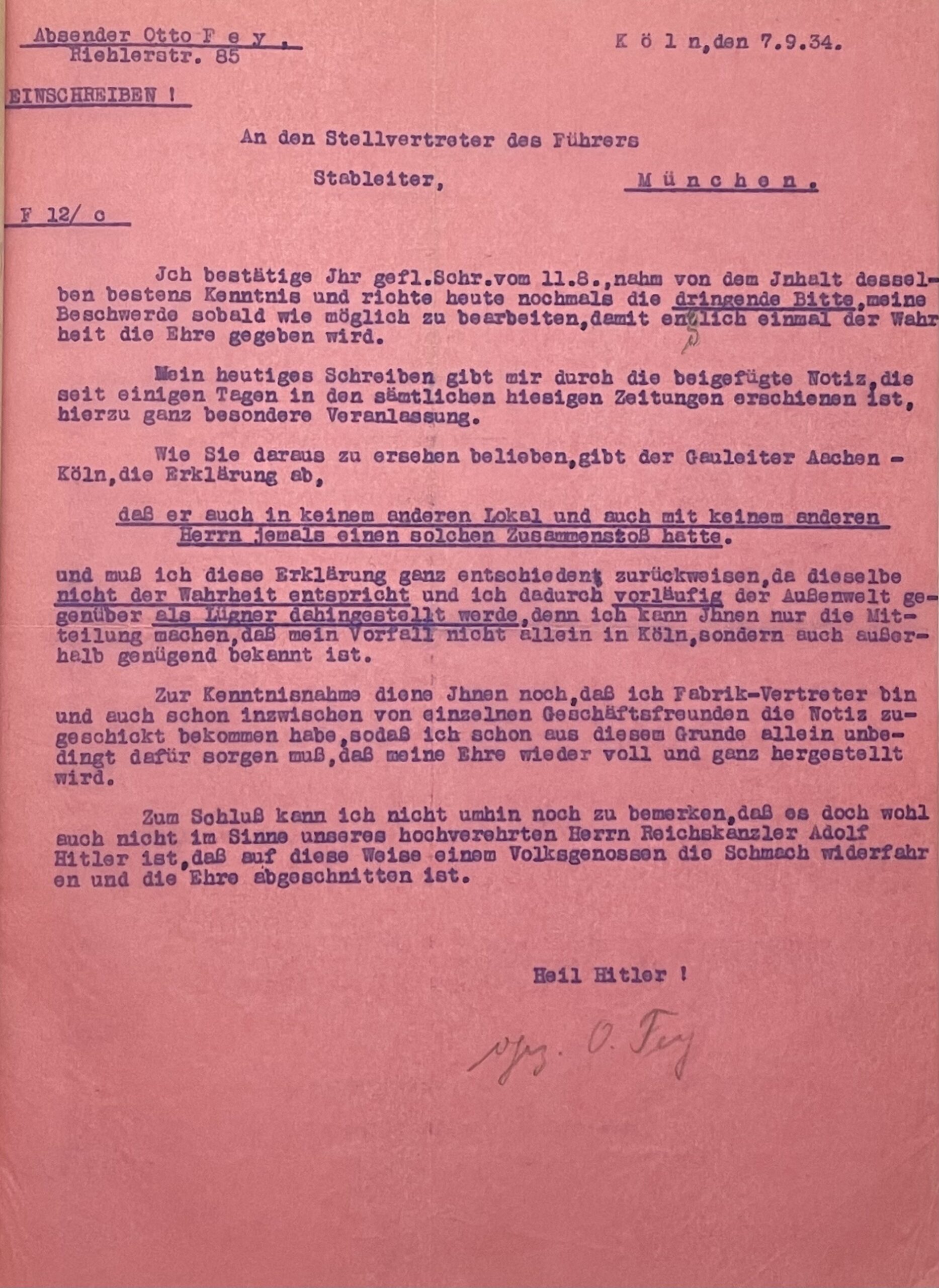

In 1934, a conflict arose between the Funken member Otto Fey and the Cologne Gauleiter (regional Nazi leader) Josef Grohé.

Conflicts over the club chairmanship existed for years. The Nazi Party Ortsgruppenleiter (local group leader) Hermann Ihle also sought the position – unsuccessfully.

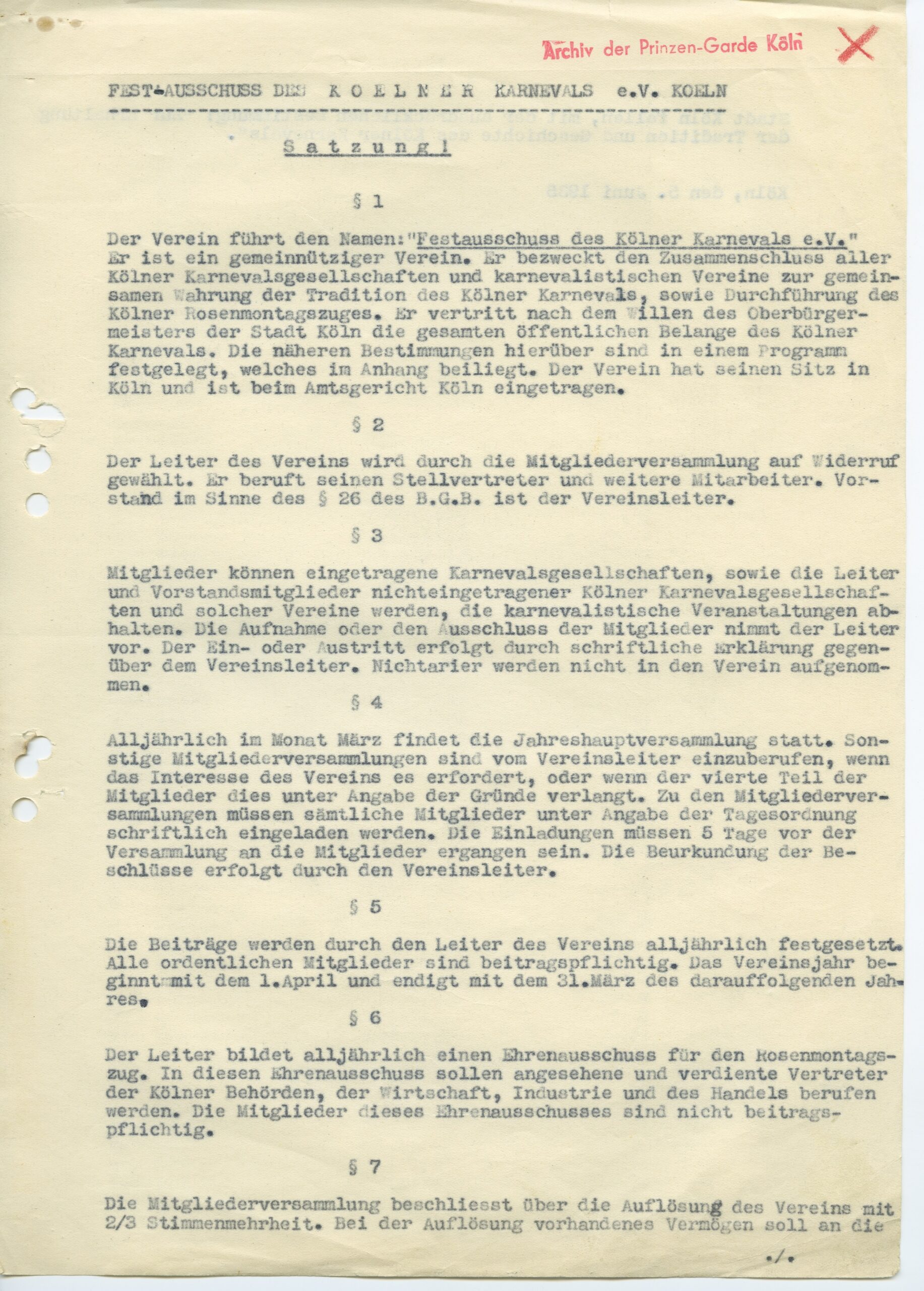

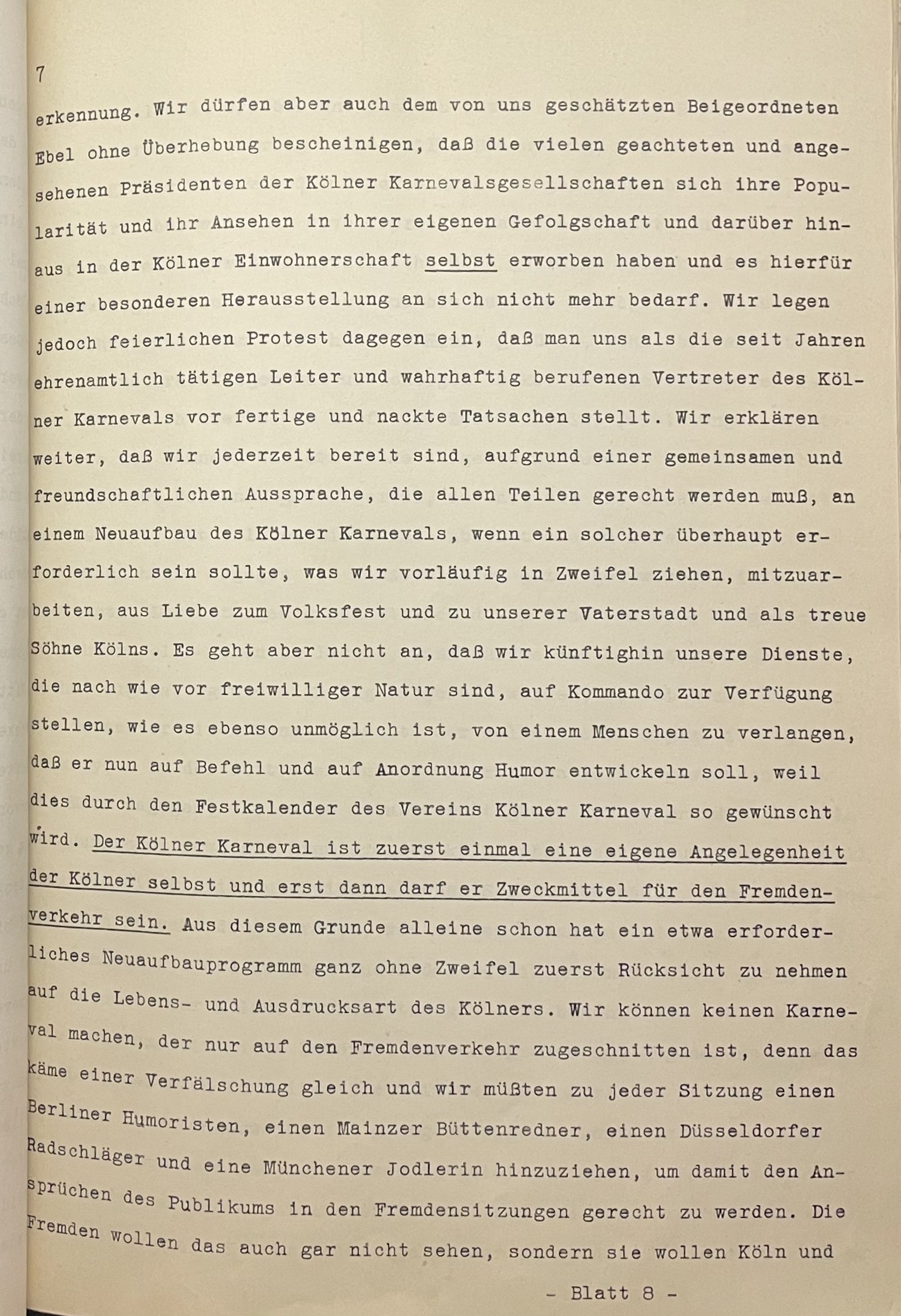

In June 1935, the festival committee introduced an ‘Aryan paragraph’ to the club statutes. However, the criticism of Funken members was directed at other aspects of the new regulations.

In such disputes, the Nazi authorities and the club would reach a mutual agreement – partly because both sides benefited from the Carnival. Originally an event dominated by the middle class, under National Socialism the Carnival became a folk festival for broader sections of the population.

The associated upswing benefited not only the Rote Funken, but also the Nazi authorities, who used the festival for propaganda purposes, as seen here in the picture during a performance by the Funken at a major event organised by the Nazi organisation Kraft durch Freude (Strength Through Joy) in 1935.

The Gleichschaltung (enforced conformity) of the Rote Funken is a prime example of how individual members exploited the new political order for their own benefit and how the club struggled to achieve a common stance on the regime. Such individual actions have been intensively researched since the 1990s, which has changed how we view society under National Socialism.

How historians view society under National Socialism has thus strongly evolved. This is linked to a changed understanding of the Nazi era as a whole. Scholars are increasingly asking questions about how Germans reconciled their everyday lives with the regime, what incentives were created for them, and how individuals benefited from Nazi rule.

The future permanent exhibition at the NS-DOK will also adopt this perspective on National Socialism.

What would you find particularly interesting in this regard?

Multiple answers are possible.

Here’s what you said:

Or do you have a completely different question that interests you?

Continue through the exhibition. The tour carries on in the room about the Gestapo.

Credits:

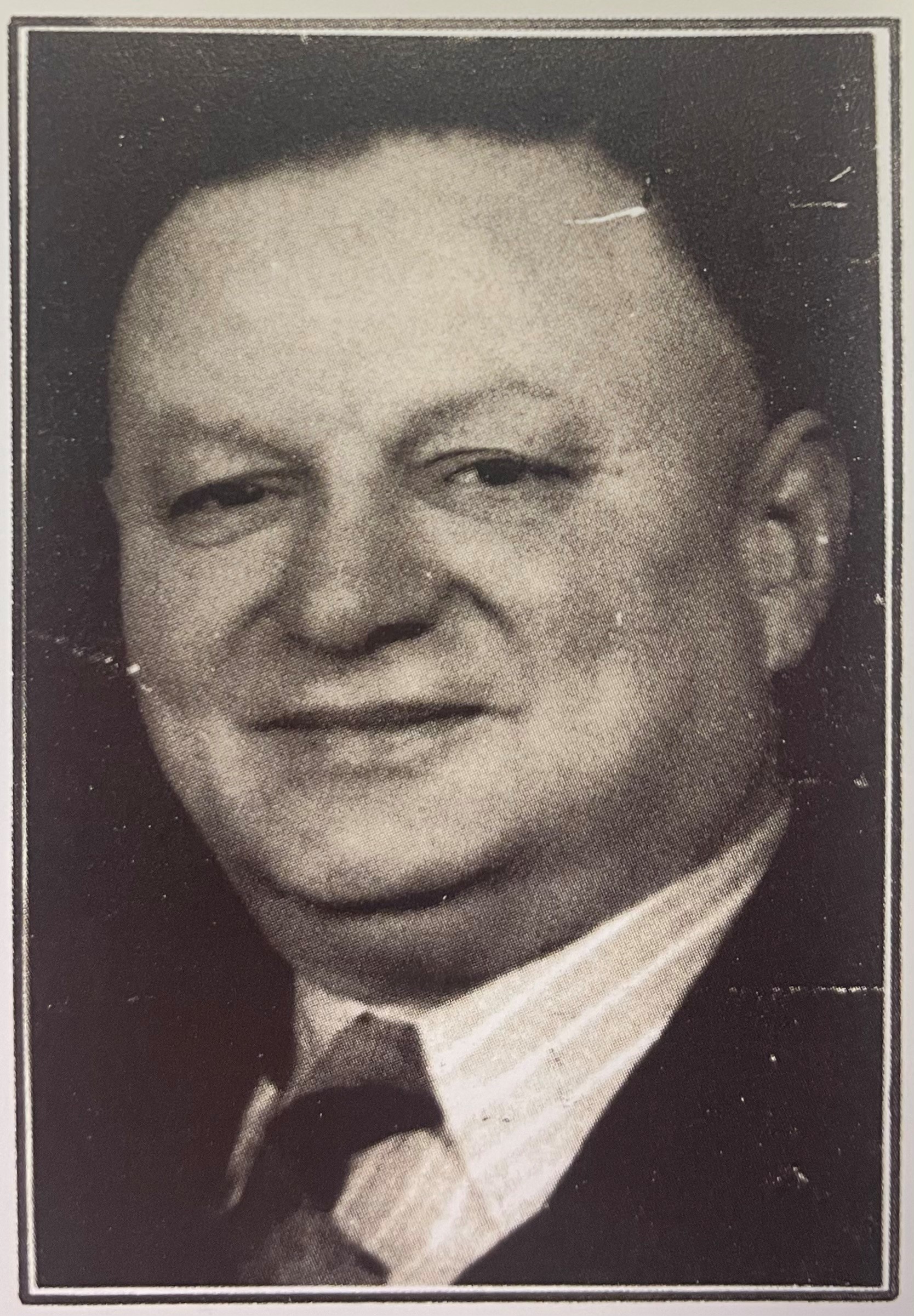

1. © Rheinisches Bildarchiv rba_d022816_78; 2. & 7. Rote Funken on the Hindenburg Bridge, 1934 © NS-DOK; 3. © private; 4. Directives for the Rose Monday Parade issued by the Cologne Carnival Festival Committee© Private archive Werner Liessem; 5. Rose Monday Parade 1934 © NS-DOK; 6: Rose Monday Parade 1935 © NS-DOK; 8. Hermann Ihle © Archive of the Rote Funken; 9. Wilhelm Schneider-Clauß © Archive of the Rote Funken; 8. Club statutes of the festival committee, 1935 © Private archive Werner Liessem; 10. Criticism of the club statutes, 1935 © Archive of the Rote Funken; 11. Otto Fey © Archive of the Rote Funken; 12. Letter to Rudolf Hess © Archive of the Rote Funken; 13. Performance by the Funken at a major event organised by the Nazi organisation Kraft durch Freude in 1935 © Private archive Werner Liessem; 14: Float of the Roten Funken, 1934 © NS-DOK; 15. Rose Monday Parade, 1935 © NS-DOK