You can see this photo in the exhibition space as a large-scale image. Neither the photo nor the highlighted elements …

- the flags

- the spectators

- the marching men

- the VIP stand

… are explained. This is problematic.

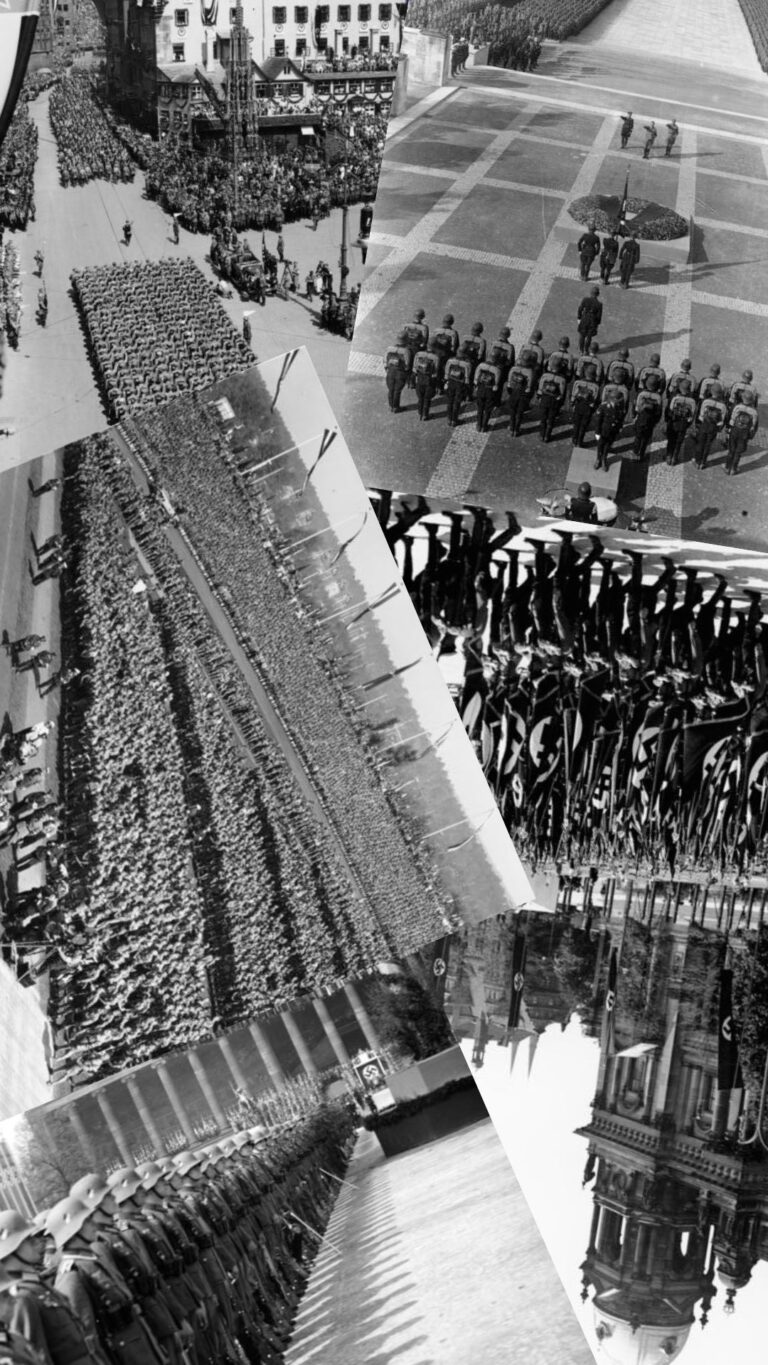

This image surely reminds you of many other photos you have seen from the Nazi era.

They all originate from celebrations and large events organised by the Nazi regime. What they have in common is that they portray an idealised image of Nazi society.

This self-image was constantly reinforced on numerous occasions and disseminated through millions of photographs and movie recordings. To this day, these images continue to shape the perception of the Nazi dictatorship.

If these images are shown like here without commentary and not identified as idealised self-portrayals, they can encourage false assumptions: they can be understood as a reflection of reality under National Socialism.

But society under National Socialism was not a harmonious unity that stood unanimously behind its leadership.

By adding contextual information, the photo no longer simply reiterates the self-portrayal of the Nazi regime, but can contribute to an understanding of the Nazi dictatorship. This can happen in various ways.

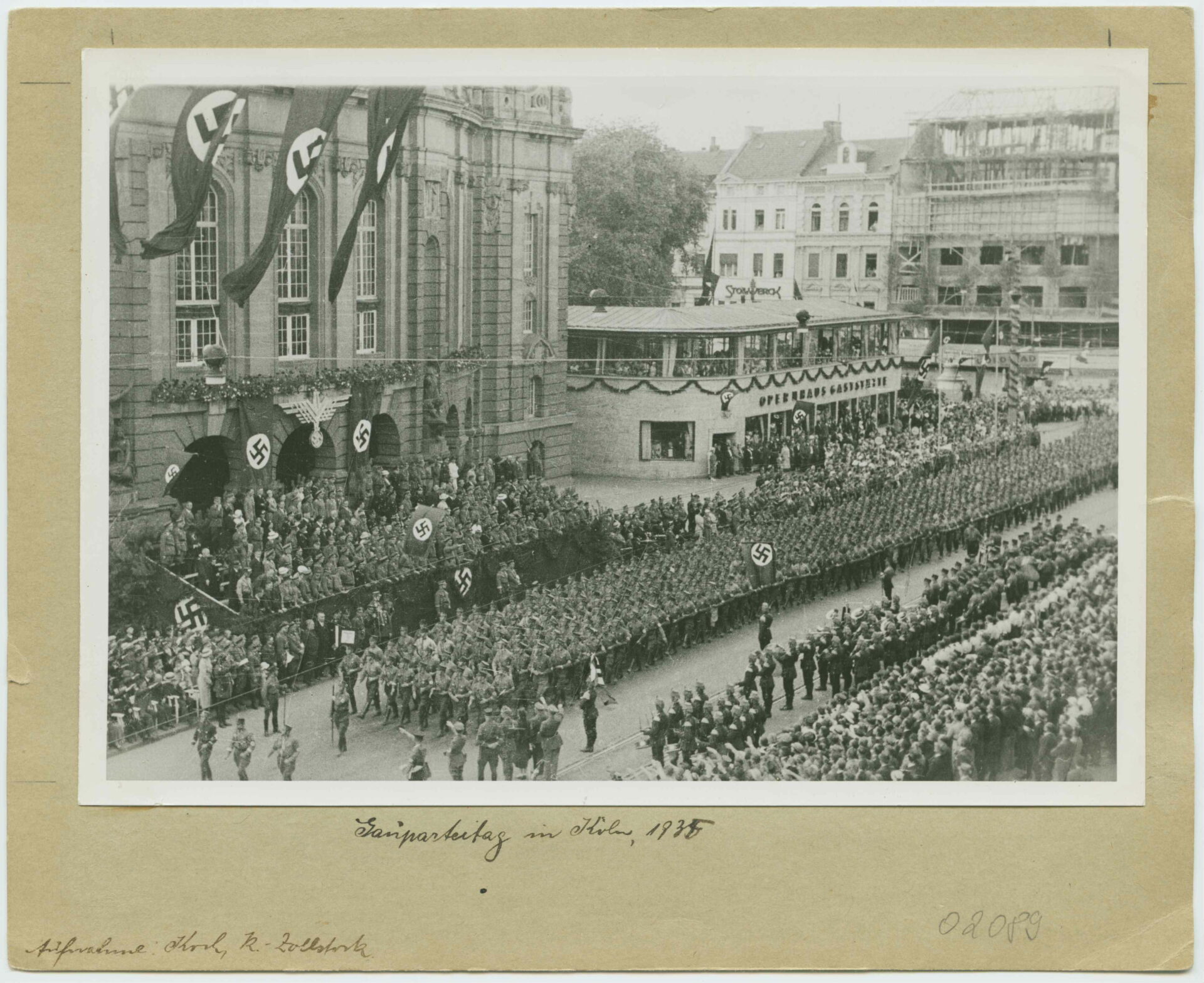

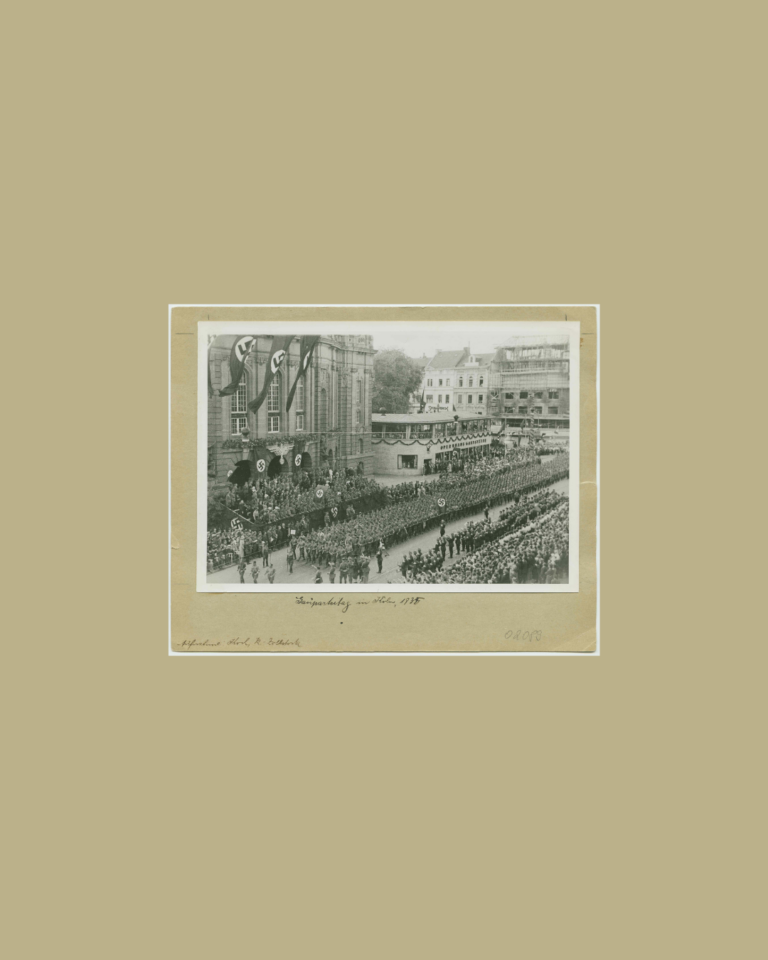

One option is to print the photograph as it appears in our collection. This draws less attention to the aesthetic composition of the image and instead makes the photograph more visible as a source.

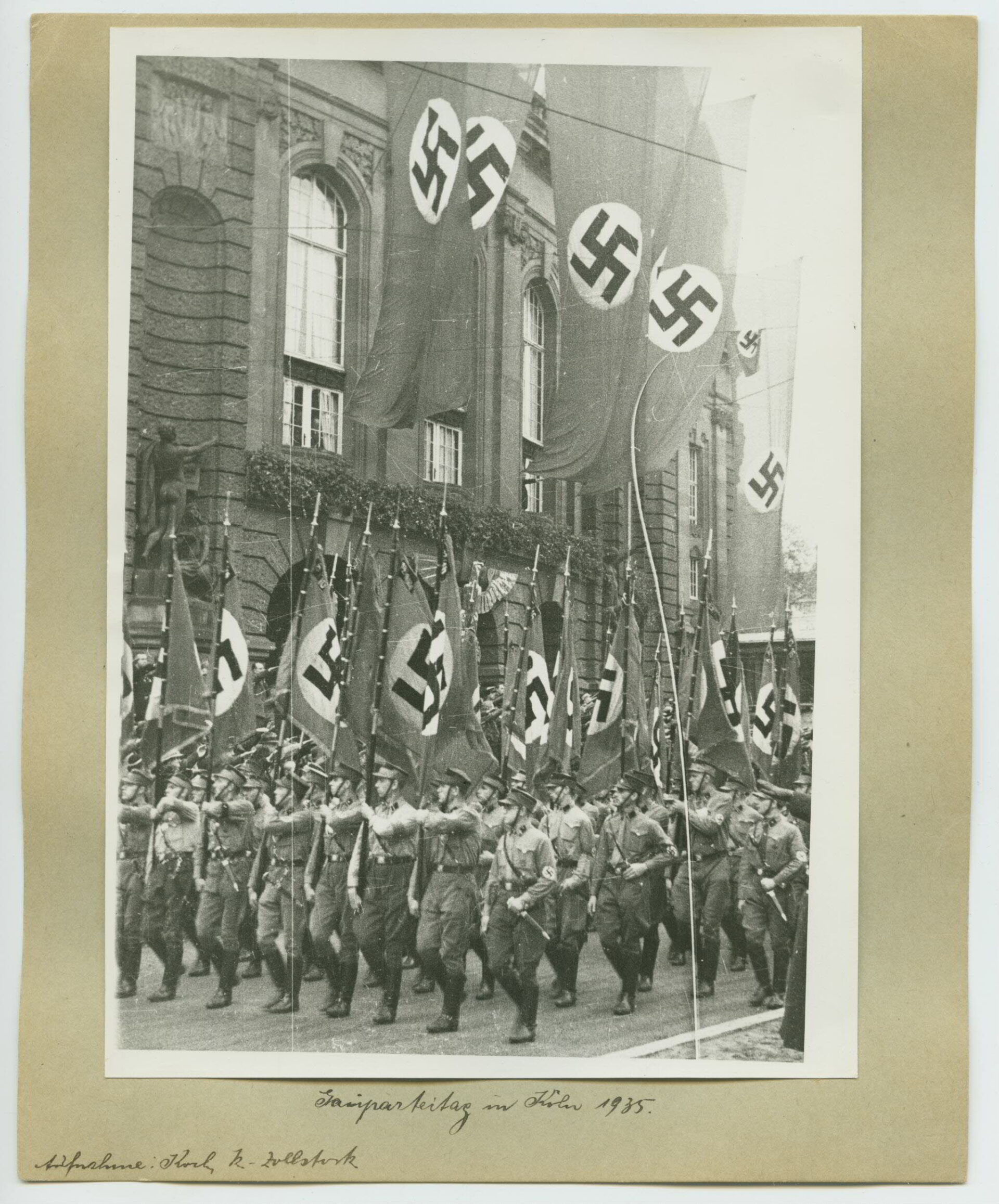

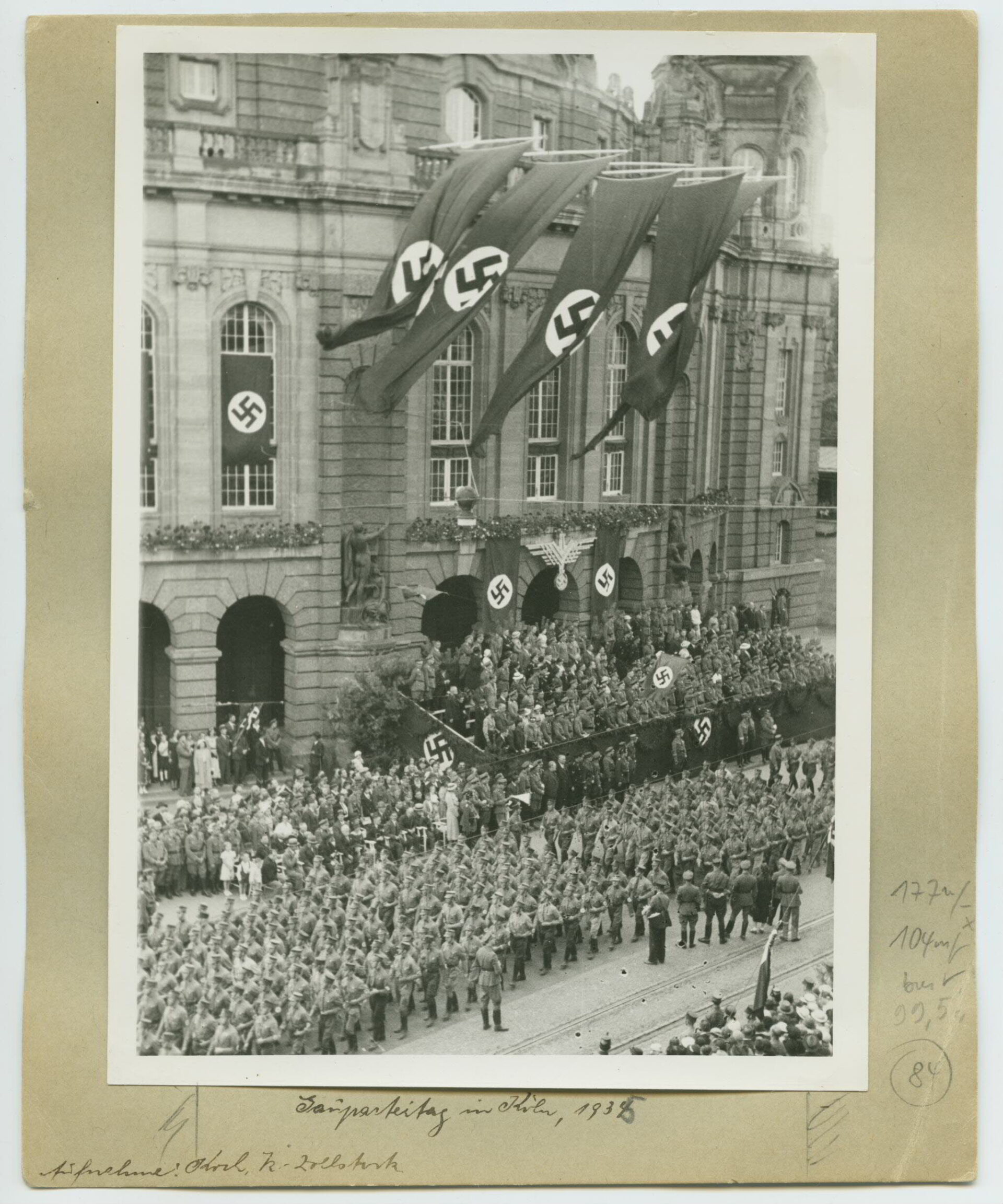

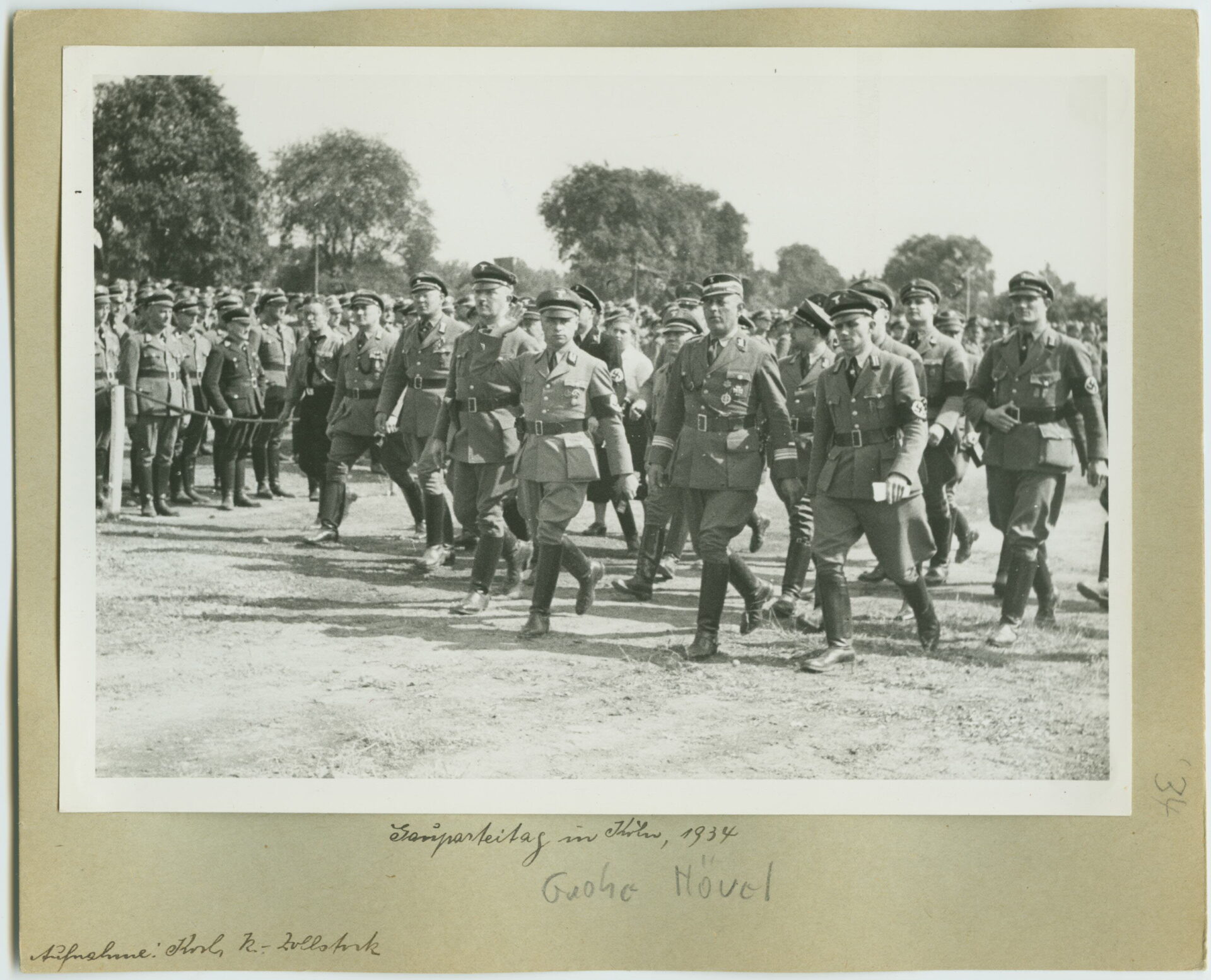

The original photograph is, of course, much smaller than the one in the exhibition space; it is about the size of a postcard and mounted on brown cardboard.

It shows a parade in front of the opera house on what is now Rudolfplatz in Cologne’s city centre. This march marked the end of the NSDAP district party conference in the summer of 1935. The photograph was taken by Helmut Koch, who in the 1930s worked as a photojournalist for well-known Cologne magazines.

It is not the only picture Helmut Koch took of this march in front of the opera house.

His photographs are part of a documentary photo collection from the 1930s and 1940s, which was probably compiled by the long-standing director of the Haus der Rheinischen Heimat (later the Cologne City Museum). The photographer Helmut Koch must have reproduced his photos, and the director must have considered them so important that he glued them – along with hundreds of other images – onto cardboard and provided them with (sometimes incorrect) information about the subject and photographer.

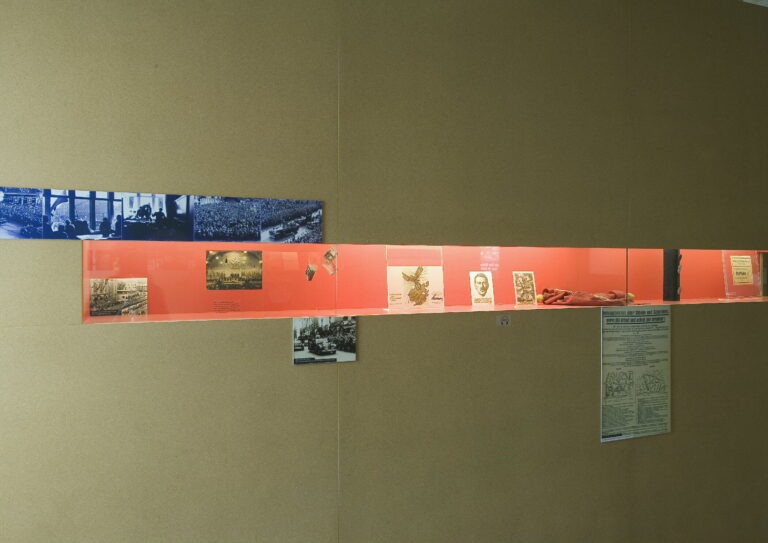

Now take a look at the display case to the right of the large photograph. The same photograph from the district party conference is presented here again as a print: with the exhibition text, ‘March in front of the opera house at the Gau party conference in 1935’ (correct: district party conference).

The brief caption provides a context for the photograph: occasion, time, and place. However, do you know what an NSDAP district party conference was and what happened there? You may select multiple answers.

Correct: Nazi officials gave speeches and Nazi organisations held parades. There was also a leisure programme. The ‘dead of the Nazi movement’ were honoured and a torchlight procession took place in the evening. At the same time, illuminated convoys of ships sailed across the Rhine.

It is incorrect that Hitler always attended. Some of the scheduled events were subject to a fee.

To prevent images of Nazi events from becoming iconic representations of Nazi society, the photo from the 1935 district party conference can be combined with other materials that show what an NSDAP district party conference actually was.

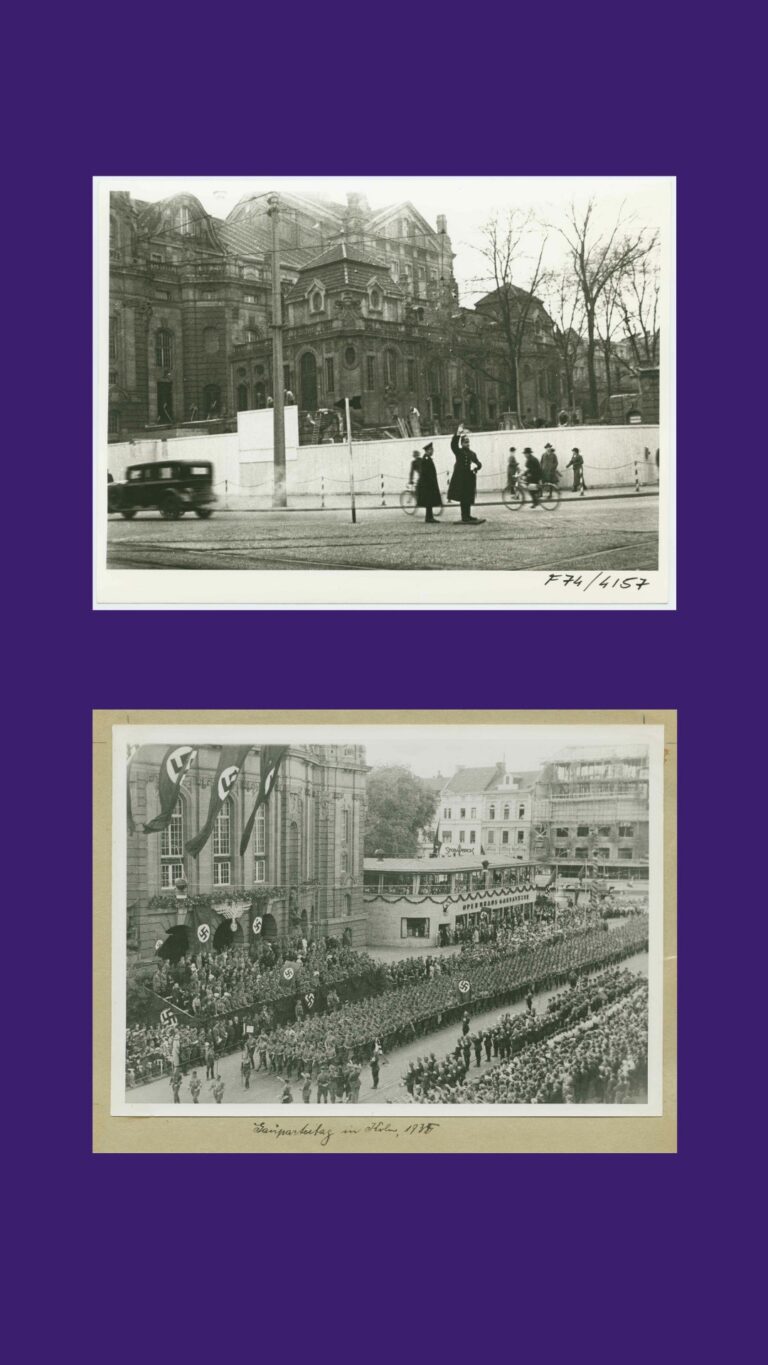

Lastly, the photograph from the district party conference can also be used to show that these events were exceptional situations in the day-to-day life of the 1930s.

Here you can see the same photo alongside another image showing the area of the event in front of the opera house on a typical day during the Nazi era.

This makes it easy to see what the city ordinarily looked like and that it was only decorated and beflagged on special occasions.

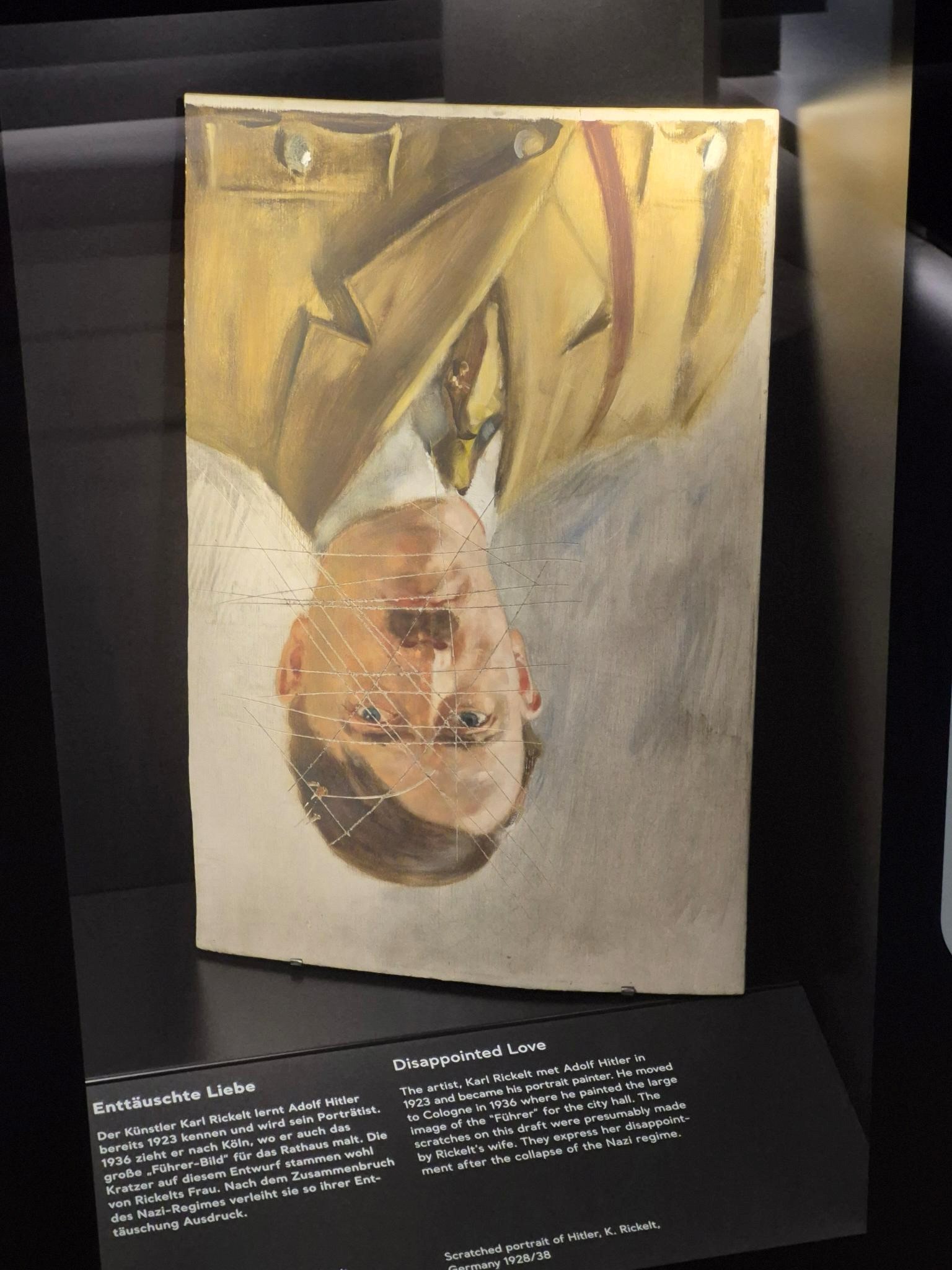

The question of how Nazi propaganda can be presented without reinforcing or affirming it has preoccupied curators, filmmakers, artists, and teachers for decades.

Here you can see how other memorial sites and museums deal with propaganda material.

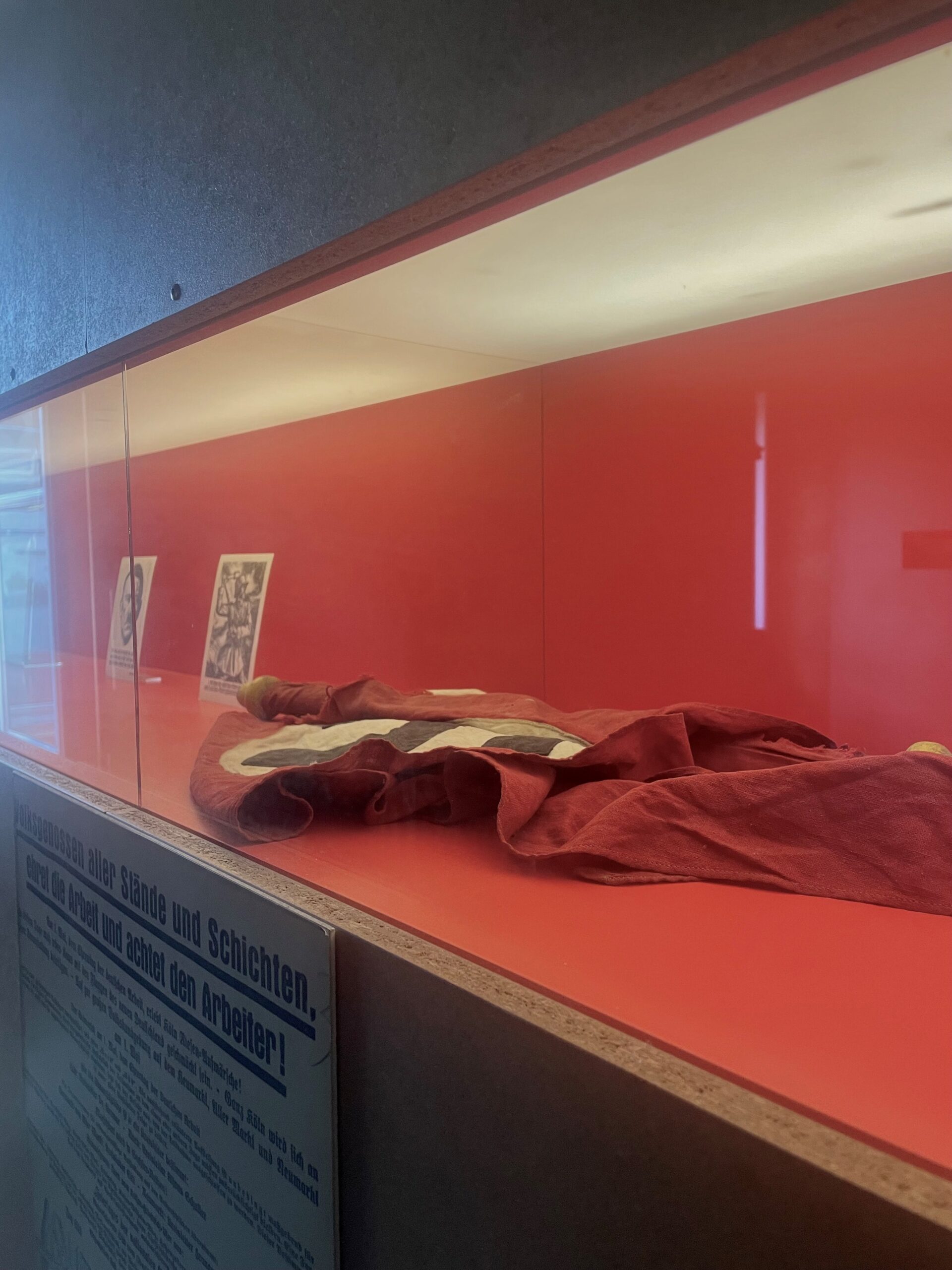

Continue through the exhibition on the second floor. There you will immediately encounter a problematic portrayal of a swastika.

Credits:

1: © private; 2. Parade in front of the opera house, 4 August 1935 © NS-DOK; 3. March of the SA in Nuremberg, 1934 © Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-K0326-0503-003 / CC-BY-SA 3.0; 4. March Kreis V Berlin 1936 © Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-2004-0812-500 / CC-BY-SA 3.0; 5. Reich Party Congress 1934 © Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-2004-0312-504 / CC-BY-SA 3.0; 6. Reich Party Congress 1934 © Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-04062A / Georg Pahl / CC-BY-SA 3.0; 7. Lustgarten Berlin 1936 © Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-P022058 / CC-BY-SA 3.0; 8.-10. Parade in front of the opera house, 4 August 1935 © NS-DOK; 11. © Rheinisches Bildarchiv, rba_d003249; 12. District party conference, 4 August 1935 © NS-DOK Bp 7143; 13. Pin of the district party conference © private; 14. Westdeutscher Beobachter, 02.08.1935; 15. Westdeutscher Beobachter, 4 August 1935; 16. Parade in front of the opera house, 4 August 1935 © NS-DOK; 17. Opera house 1934 © NS-DOK; 18. Obersalzberg Documentation Centre © Obersalzberg Documentation Centre / Kradisch; 19. NS-DOK © private; 20. Cologne City Museum © private; 21. Buchenwald Memorial © Claus Bach, Buchenwald Memorial; 22. Wewelsburg Castle © Wewelsburg Castle / photographer: Lina Los; 23. Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg © Stefan Meyer / Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg