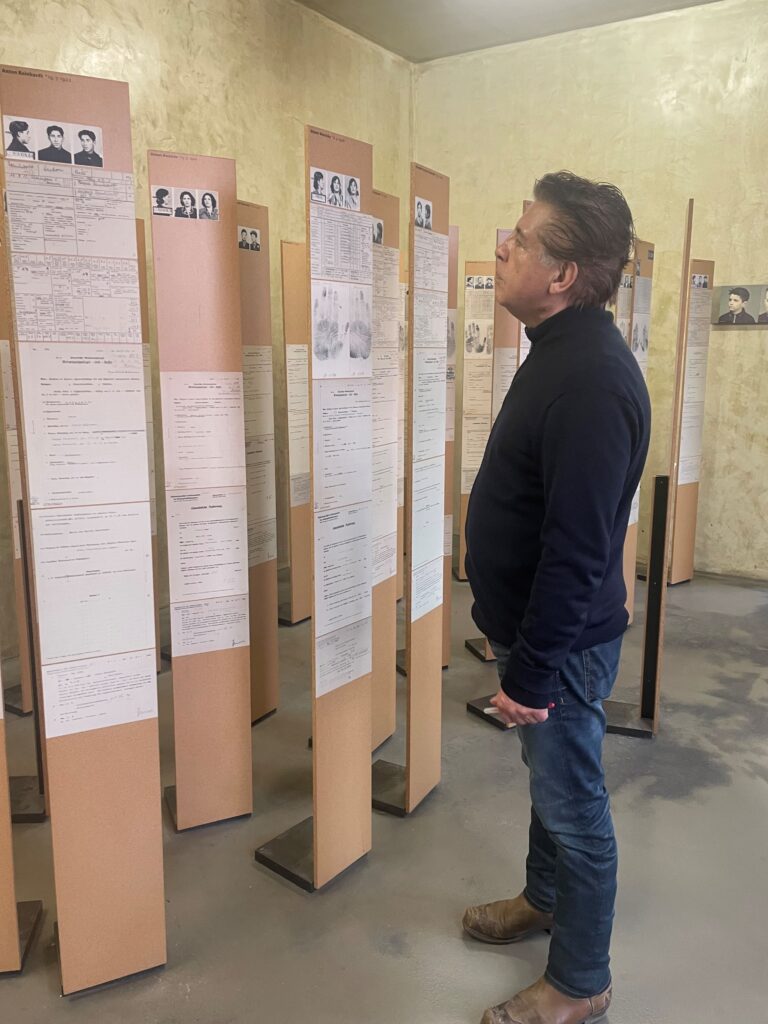

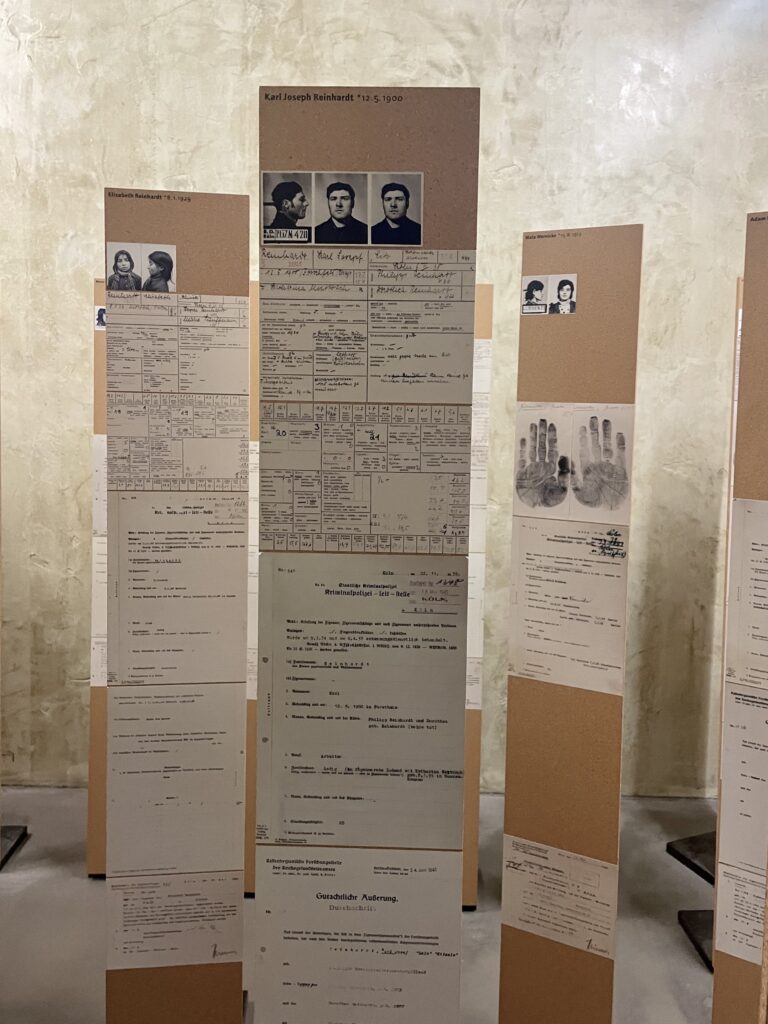

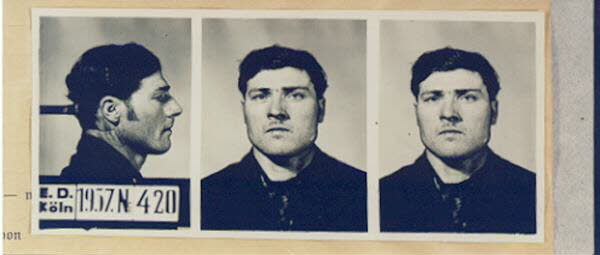

Here you can see numerous mug shots, hand and fingerprints, and the results of body measurements. In this respect, each display stand documents the history of the persecution of Cologne’s Sinti and Roma under National Socialism.

Yet they show this history from a specific perspective: almost all the photos and documents in this room come from Nazi authorities, the Criminal Police, or the Racial Hygiene Research Centre, a pseudo-scientific institution of the Reich Health Office.

Take a moment to look around.

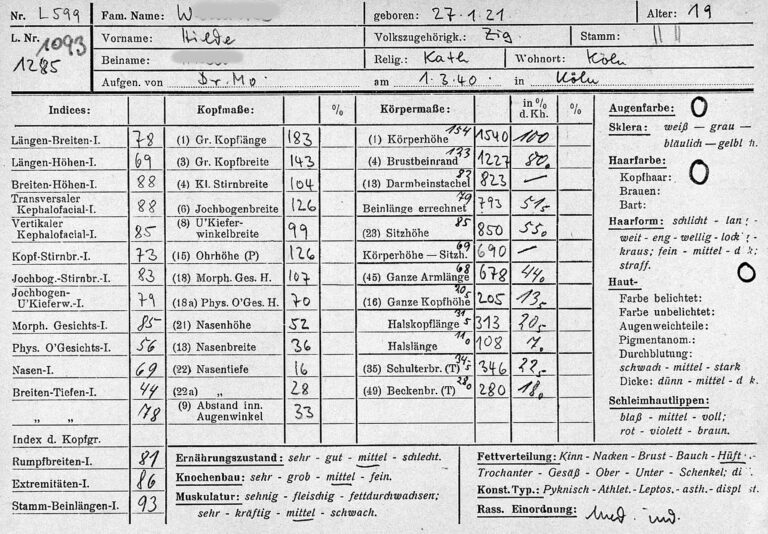

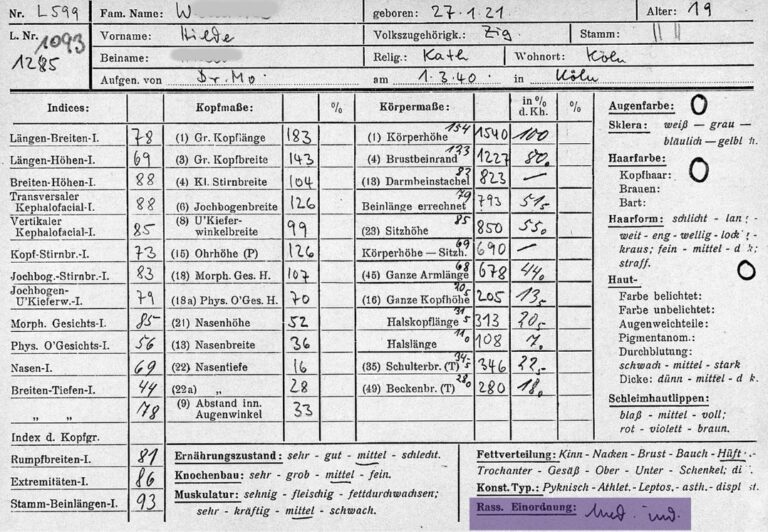

Some of the index cards from this Racial Hygiene Research Centre contain more than 20 head and body measurements of Sinti and Roma people. These measurements were made under false pretences or by force.

Also noted are the results of the degrading ‘examination’: in the lower right section of the index card, each person was assigned to a group according to Nazi racial ideology (‘racial classifications’). These categories played a role in determining their further persecution.

Several photographs in the room show institute employees performing the degrading measurements. One photo shows them examining a child in Cologne-Bickendorf, where a few years earlier the city had set up a camp to centrally house the Sinti and Roma in Cologne.

Would you want to see these pictures in an exhibition, or would you rather not?

Position the slider.

The fact that the sources in this room only reflect the perspective of the persecuting authorities is problematic. They merely provide insights into specific moments of the persecuted persons’ lives, while the rest of their biographies and their own perceptions remain unknown. Moreover, the documents contain derogatory data and terminology.

We will show you an example of how the use of other materials can change our view of the lives of persecuted people.

Can you find the display stand about Karl Josef Reinhardt?

The documents it displays trace the key stages of his persecution: Karl Josef Reinhardt was registered by the Criminal Police in 1937, subjected to a racist examination, and ultimately deported to occupied Poland in May 1940.

We would like to show you a different picture of him.

Here you see Karl Josef Reinhardt in the 1950s with his family and friends at the caravan site where he lived.

Karl Josef Reinhardt was born in Alsace in 1900 and was the cousin of the famous jazz musician Django Reinhardt. He lived with his wife Katharina Mettbach in Cologne. Of the family’s twelve children, only six survived the Nazi persecution.

To avoid telling the story of the persecuted solely from the perspective of the Nazi authorities, we need private sources that have been voluntarily provided. This poses challenges for memorial sites and museums. To be sure, they purposefully collect material from private collections, such as letters, diaries, and photographs. But even so, stories like those about Karl Josef Reinhardt – which we have thanks in part to an interview project carried out by the Sinti community itself – remain the exception.

In the 1990s, compiling this wealth of biographical examples of the persecution of Sinti and Roma, which until then had been largely concealed, was a progressive approach.

Today, however, achieving a dignified portrayal of the persecuted – one that is less determined by external actors – has become a more pressing issue than merely bearing witness to the crimes. And it is precisely the relatives of the persecuted and of people targeted by discrimination today who criticise the ‘bureaucratically determined’ materials.

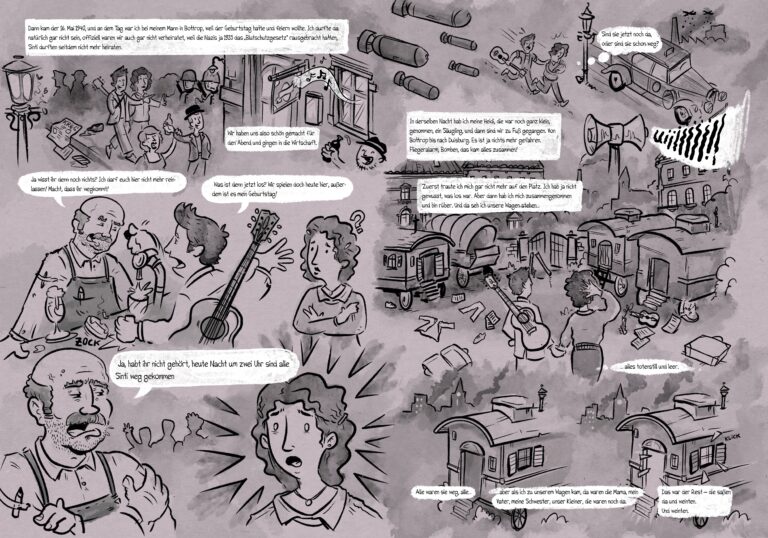

The fact that without appropriate sources some aspects of life cannot be portrayed from the perspective of the persecuted creates a problem that is not easily resolved. This is why some museums resort to fiction and find creative formats in which biographies can also be enhanced.

In its catalogue for an exhibition on the Nazi persecution of Sinti and Roma, the Kultur- und Stadthistorische Museum Duisburg published a graphic novel about the biography of the Sinta woman Hildegard Lagrenne. The narrative complements the official sources in the exhibition with a personal perspective.

What do you think: what should museums do when private materials are the exception?

You can only choose one answer.

Here’s what you said:

I have a completely different idea, namely…

Continue through the exhibition. It carries on in the next room.

Credits:

1. © NS-DOK; 2. © NS-DOK / Michael Wiesehöfer; 3. Index card of Hilde Wernicke © Bundesarchiv R 165; 3. Measurements of the Racial Hygiene Research Centre © Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1987-107-30 / CC-BY-SA 3.0; 4. Markus Reinhardt in the exhibition © NS-DOK; 5. © NS-DOK; 6. File of Josef Wernicke © HStAD BR 2034 Nr. 157; 7. Reinhardt family, 1950s © private property of Markus Reinhardt; 6. Philipp Reinhardt © private property of Markus Reinhardt; 7. Music group of Philipp Reinhardt © private property of Markus Reinhardt; 8. © Rheinisches Bildarchiv rbd d022816-88; 9. Graphic Novel Alles totenstill und leer © Kultur- und Stadthistorisches Museum Duisburg / Jonas Heidebrecht

Videos:

1. Philipp Reinhardt, intreviewed by Werner Jung and Nina Oxenius, 15 September 1992 © NS-DOK; 2. Markus Reinhardt, interviewed by Krystiane Vajda, 2 December 2019, project: Klänge des Lebens. Der Weg der Überlebenden © NS-DOK; 3. Alexa Hennings: Die Heimkehr. Der Weg der Sinti-Familie Reinhardt von Auschwitz nach Köln © Deutschlandradio

With the kind support of: