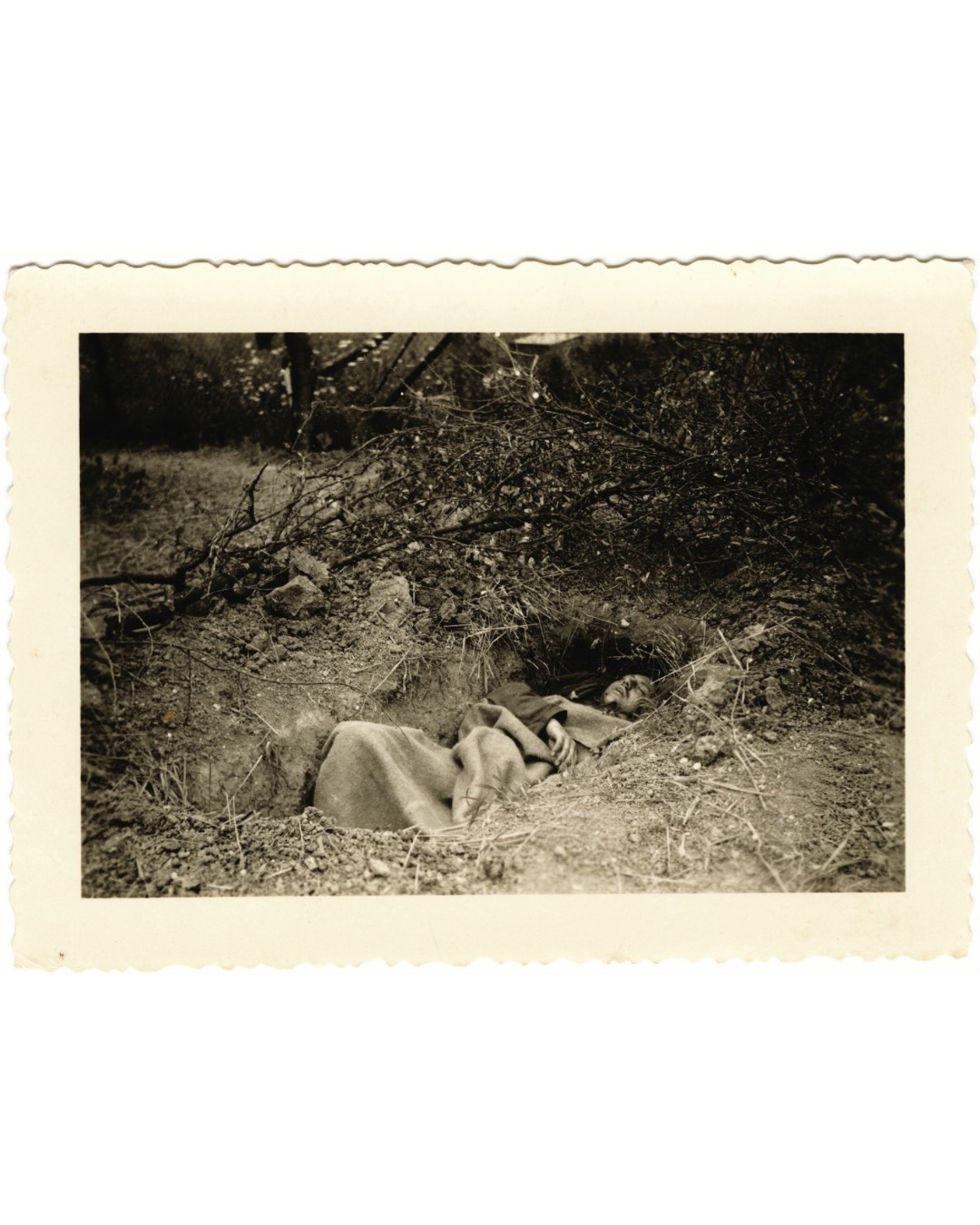

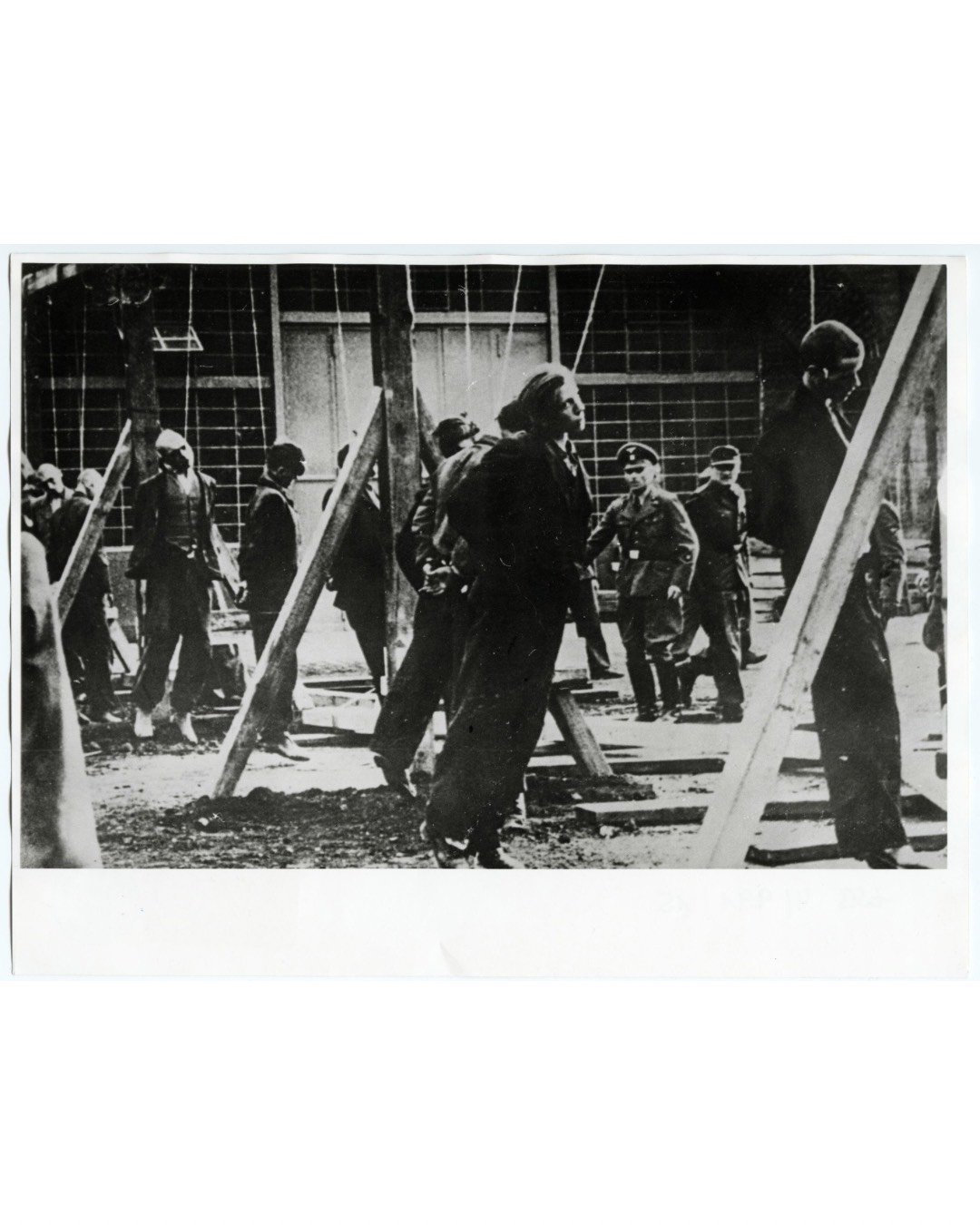

Before at this spot you could see a picture of three men, presumably taken in Belarus. They are hanging from a gallows with their arms tied behind their backs, and they are probably already dead. The photo is taken in such a way that two of the faces can be seen.

However, we do not know the identity of the murdered men. Nor can we say why they were hanged or who the perpetrators were. What is certain is that someone purposely captured their deaths on camera.

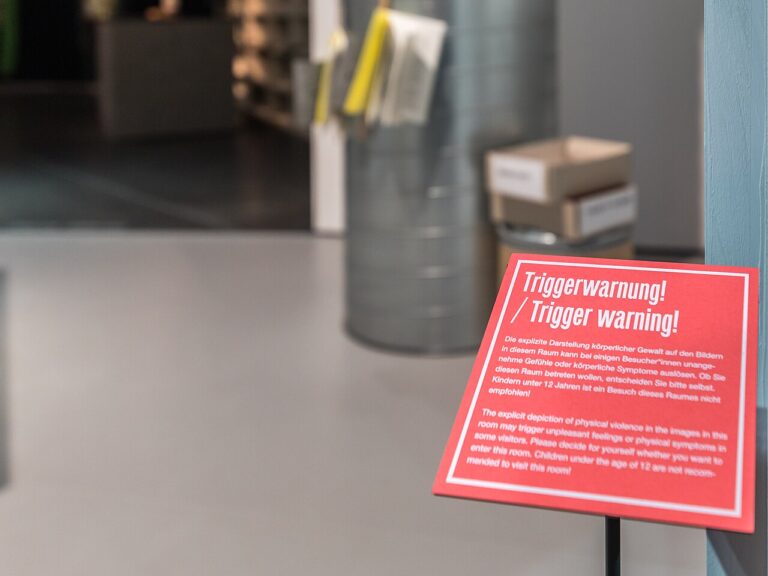

We have decided to cover up this image because it shows victims of a violent crime in a degrading manner. We also lack the necessary information to contextualise the image.

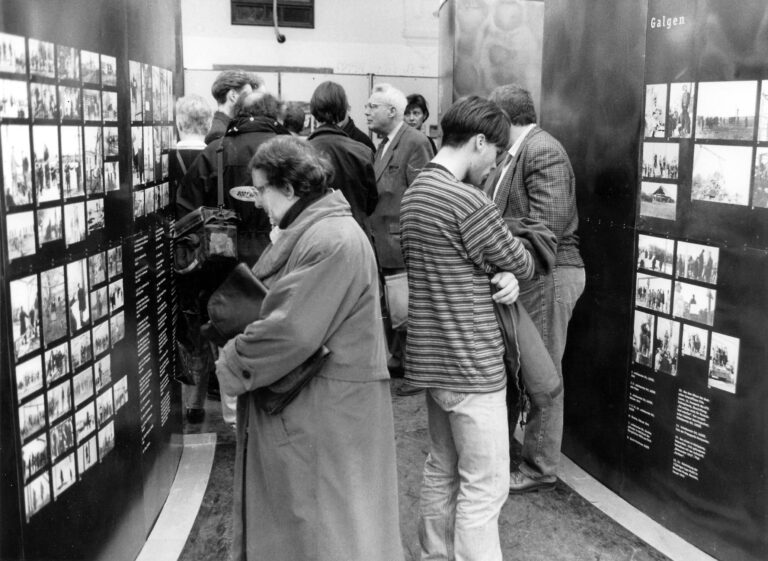

For a long time, curators dealing with National Socialism used drastic photographs to shock visitors – in part because some of the crimes committed by the Nazis were still unknown or being denied.

Images of acts of violence served as evidence and educational tools, like here at the first Wehrmachtsausstellung (Wehrmacht Exhibition) in Munich in 1997.

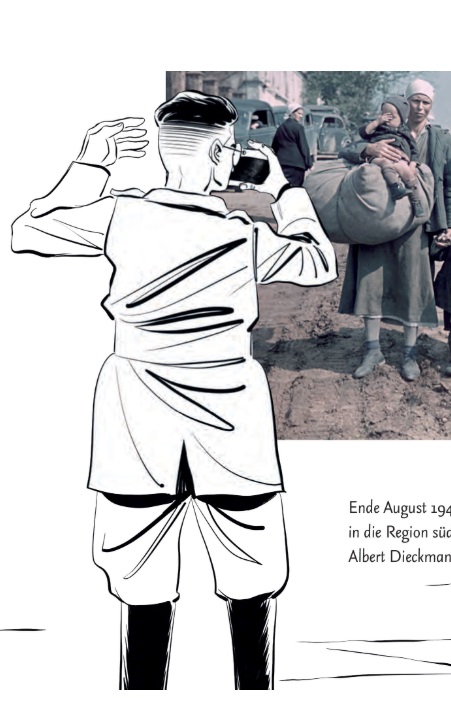

In recent years, the way we view historical photographs has changed, especially when they depict violence. Photographs are now much less understood as images of the past that simply speak for themselves.

Instead, they must be interpreted, because people took them in specific situations for a specific purpose. And this shapes the subject matter of the photograph.

In addition, violent photos have raised awareness of the dignity of victims: for such images, people were involuntarily placed in degrading situations and positions. And they cannot decide for themselves whether the photos of them should be distributed.

But viewers of violent images are also increasingly being considered. Being overwhelmed and shocked does not automatically trigger empathy with the victims. Rather, it can cause uncertainty: without information, viewers are left alone with the question of how to categorise the violence and what reactions to it might be appropriate.

Whether and how violent photos can (still) be shown has since become an issue of great debate.

Here and in the adjacent rooms, there are further depictions of violence that we did not cover up. You can see some of them again here. However, you see the photos blurred and accompanied by explanatory information. Using the slider, you can decide whether and to what extent you want to reveal the photograph.

You decide: What would you cover up? And what should still be shown? Scroll directly past them if you do not want to see the images.

Would you like to tell us anything else about your decisions? What goes through your mind when you think about this topic?

Thank you!

In your opinion, what should be required when showing depictions of violence in museums?

You can select multiple answers.

Here’s what you said:

Thank you for your interest! You will find all the results of the votes on your way back to the staircase in the corridor.

Credits:

1. © NS-DOK; 2. © dpa 498465965; 3. © Staatsarchiv Würzburg, Gestapostelle Würzburg 18880 a, Foto Nr. 19; 4. © Museum Berlin Karlshorst 5. © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0; 6. © YIVO RG 241-1088-6;7. © NS-DOK; 8. © NS-DOK 9. © LAV NRW R, Ger. Rep. 248/67, Bild 11